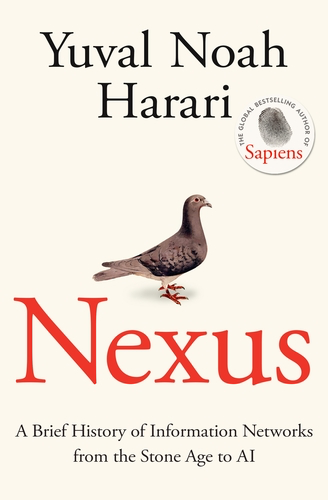

Book Review: Nexus – A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI

By Tyler Jefford

February 16th, 2026

Nexus by Yuval Noah Harari is one of those books that sneaks up on you. It starts comfortably, tracing how humans have always organized themselves around information. Stories, myths, writing, printing presses, bureaucracies. Things you already feel familiar with. Then, almost without warning, it pulls the floor out from under you and asks a much harder question: what happens when information systems stop being passive tools and start making decisions for us?

One line that stuck with me is the distinction between traditional tools and AI. Knives and bombs do not decide whom to kill. They are dumb tools. AI is different. It can process information, learn patterns, and act independently. At that point it stops being a tool and starts behaving like an agent. That framing matters, because it forces us to confront how casually we are handing over decision making power to systems we barely understand.

A recurring theme in the book is that human cooperation has always been built on shared stories. We stopped needing to know each other personally and instead learned to believe the same narratives. Religions, nations, markets, and now algorithms. The problem is that while we are extremely good at accumulating information and power, we are far worse at accumulating wisdom. We scale systems faster than we scale judgment.

That gap is where things get dangerous. Democracies do not just die when speech is suppressed. They also die when people stop listening, or lose the ability to tell signal from noise. Information networks optimized for engagement do not care whether they are spreading truth, fear, or outrage. They only care that you keep paying attention.

The most unsettling parts of Nexus are not about killer robots. They are about subtler failures. Silicon chips that create spies that never sleep, financiers that never forget, and despots that never die. Systems that can manipulate humans without ever touching their brains. Language has always shaped societies, but now computers are learning how to wield it at scale, faster and more precisely than any prophet or politician ever could.

The book makes it clear that new technologies often lead to disaster not because they are evil, but because humans take time to learn how to use them wisely. The scary part is that this time, the systems are learning faster than we are. And if AI ends up in the hands of bad actors, history suggests we should not assume wisdom will arrive in time.

This is not a book that makes you optimistic. It is a book that makes you alert. And right now, that might be more important.